Wouldn’t it be great to have a time machine so you could travel back in time and relive your greatest experiences? I think today we can make this dream a reality.

I’ve been tracking many aspects of my life over the last few years. My diet, my sleep, my activity, my exercise, my body metrics, my likes and dislikes, the music I listen to, my contacts, my conversations, my opinions, my mood, my air miles, my location, my energy levels, how I spend my money and how I spend my time, the hours I work and the time I spend in meetings, my browsing history, how often I stretch and how often I floss, how much alcohol I drink, the temperature indoors and out, the air quality in my bedroom, how much I feed the fish and the last time I changed the light bulbs … All this is recorded as data at varying levels of granularity, some of it by the minute.

There’s a word for this – and it’s not “neurosis”. They call it lifelogging. I’m a collector. I just love collecting data like other people collect comic books or Panini stickers. Is that just digital squirrelling, or do other people simply not pay as much attention to the data they’re radiating?

Data, everywhere

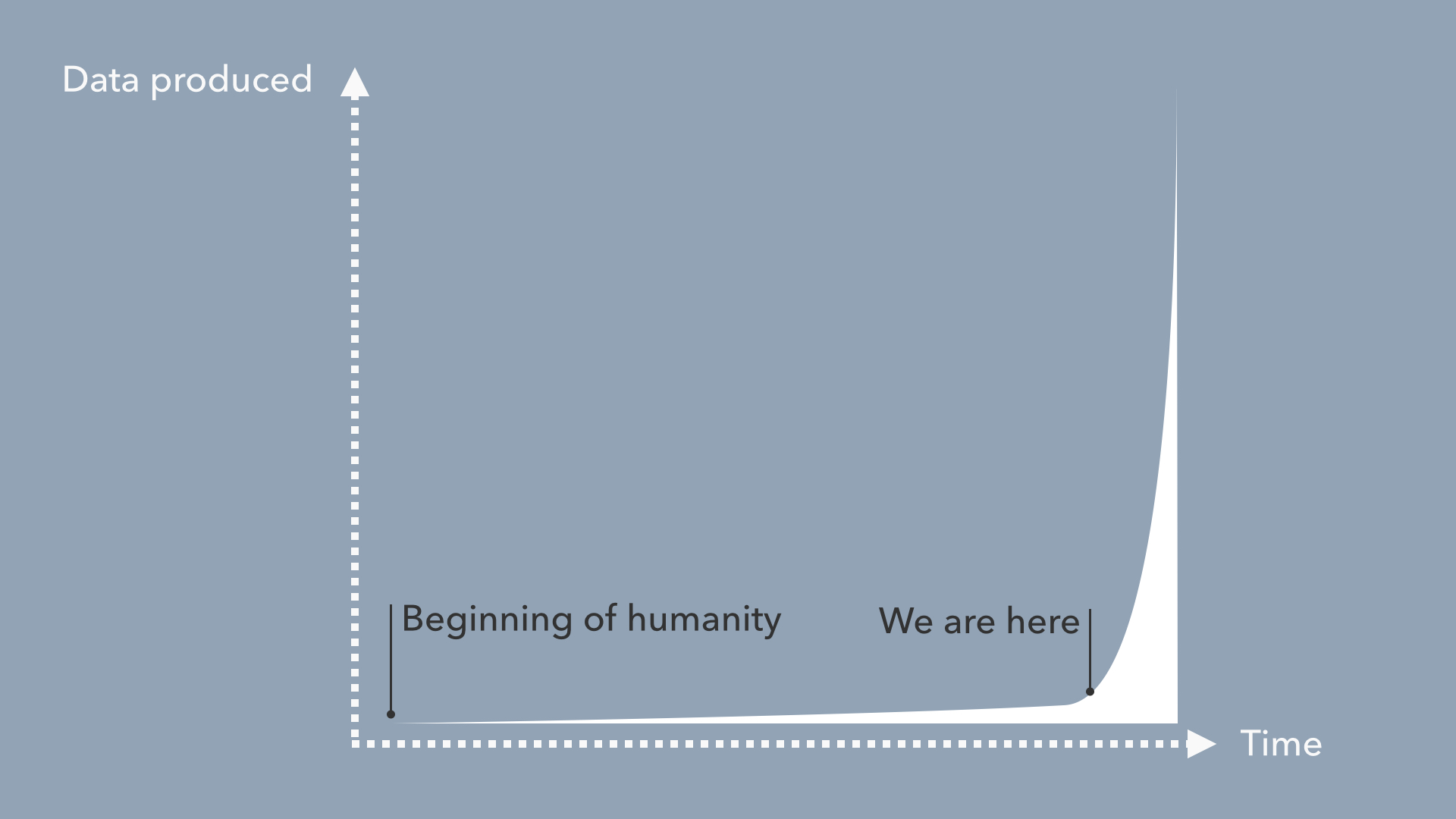

From the beginning of humanity until today, it is estimated that we have produced just over 1 Zettabyte of data. That’s 1 billion Terabytes. By 2020 this amount is predicted to grow to 35 Zettabytes – 35 billion Terabytes. This makes a pretty impressive graph, showing that we’re producing a hell of a lot of data on a daily basis and we’re not going to slow down.

Where does all this data come from? Obviously our written pieces, photographs and communications with one another make up some of it, but also every website we browse, every purchase we make on Amazon, every Snapchat we send - that’s all data. We now carry smartphones packed full of sensors and wearable activity trackers that leave behind a trail of data of literally every step that we make, as if we’re walking through newly fallen snow. The age of smart sensor-enabled objects in our homes and on our body has only just begun and already we spend most of our lives engaging with digital technology in one form or another. We live many of our everyday experiences entirely through these services. Chris Dancy, SVP at Healthways, speaks of a “data exhaust”. Data is a byproduct of our digital existence, not just for collectors like me, but for everyone.

Whether we’re aware of it or not, data defines to a great extent who we are. Through data we experience what it means to be connected – to others, to the environment and to ourselves. I want to explore one manifestation of this connectedness: our memories. Memories encapsulate our identity unlike anything else.

Digital memories

When we think about memories, one thing that springs to mind is photographs. They’re literally moments of a life captured on paper, or in pixels today.

My great-grandfather was a photographer. In his day that was a pretty unusual thing. He lived at the turn of the 19th century in a small village in Germany. With his photography he captured all aspects of life for the people of the region such as plane landings, the construction of churches, celebrations and everyday life. Many of his photographs ended up on postcards. Through his passion he took on the role of an archivist. His photographs were the village memory.

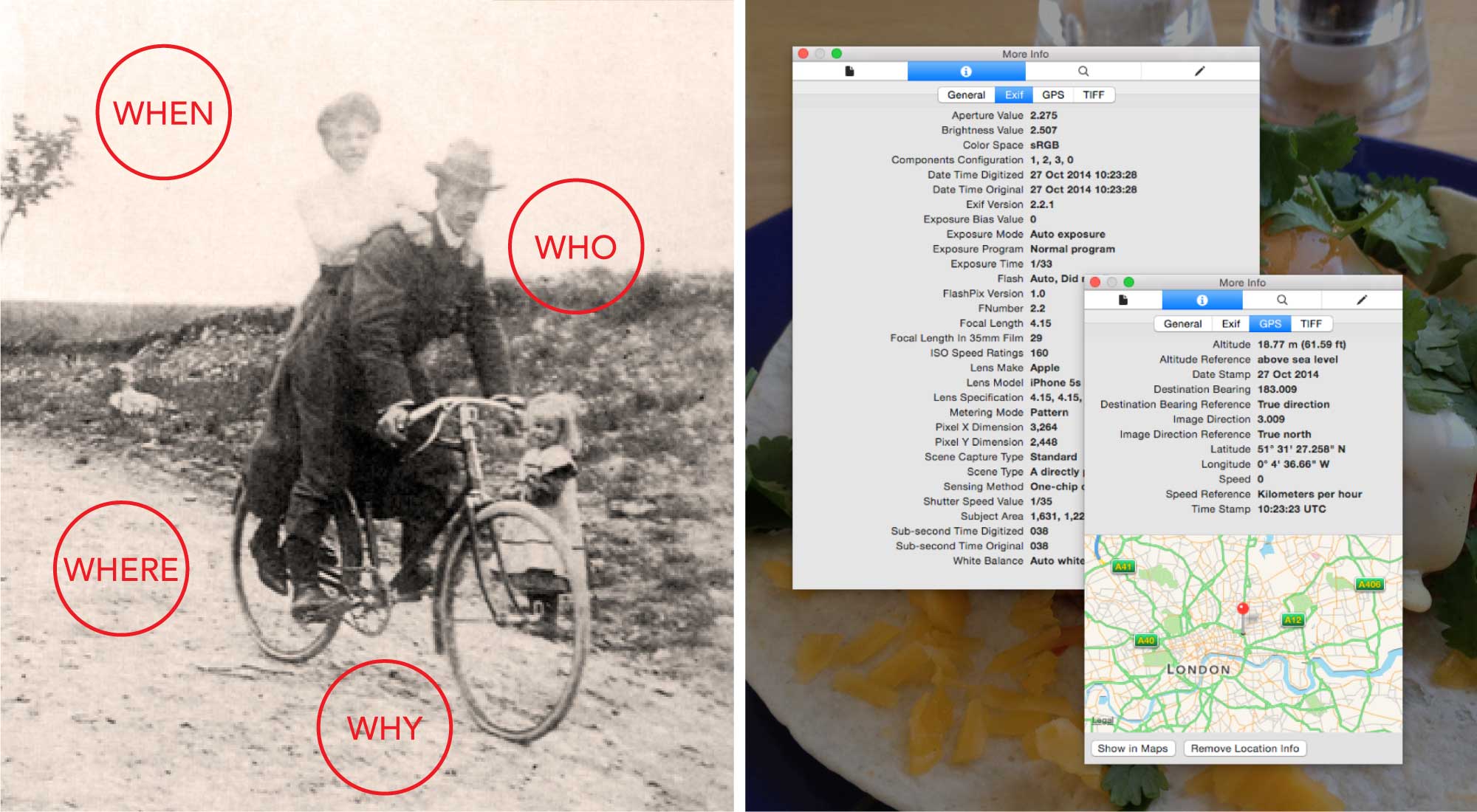

With digital and smartphone cameras today every one of us is taking on this responsibility. We’re snapping more photos than ever before. Today 350 million photos are uploaded just to Facebook every day. Yet more are sent to Instagram. When you compare my photos to those taken by my great-grandfather however, many of the pictures I take on a daily basis are no postcard material – unless you’d like to see postcards showing selfies, what I’ve eaten for lunch, whiteboards, receipts and Post-it notes. What they have in common with the captures of my great-grandfather is that they contain lots of information. The subject of a photo, the circumstances that led to its capture, sometimes the weather, people, location, and many other clues are encoded in the photo itself. In addition to this, my photos capture metadata – accurate timestamps and geolocation, for example.

We’re living in a “GoPro culture” based on the motto of a generation: “Pics or it didn’t happen”. It’s the age of the selfie, a “here I am” (or was) ethos. We’re taking photos as proof of our experiences – and our existence. When you look at the sea of smartphone lights at any event or concert, you see a manifestation of the phenomenon that, when we’re not recording our experiences, they somehow feel less real. This ‘realness’ is not only reserved for photos, more and more it applies to other data too.

Data captured from activity trackers, for example. You record your 10,000 step day with your Fitbit. You’re adding all the ingredients of this delicious home cooked dinner to MyFitnessPal. And of course you’re proudly checking – and tweeting – the route and elevation profile of your lunchtime jog in the park with RunKeeper. Data or it didn’t happen.

The name of this phenomenon is Quantified Self. A movement founded in 2008 by WIRED editors Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly. Gary Wolf in his 2010 TED talk described these tools as “mirrors” that help us with self improvement, self awareness and self discovery; and so the motto of the movement became ‘Self knowledge through self tracking’.

According to Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living”. In this spirit more and more people are actively examining their lives through health and activity trackers. It’s no longer just a niche. QS is going mainstream. Your phone has a dedicated motion processor exclusively for counting your steps, your trainers give you feedback about your performance, your watch is sending your heartbeat to your wife.

But do we actually use this stuff for self improvement, as Gary Wolf said in 2010? According to figures published by Pew Internet Research, 46 per cent of people who track their health say that it has changed their behaviour. That number means less than half of self-trackers actually find any actionable benefits. So what are the rest tracking themselves for? Like the selfie phenomenon, self-tracking feeds our desire to affirm our existence. We all want to make a mark, leave a footprint behind in the snow.

There was an interesting story in the comments section of a YouTube video about spiritual experiences in Gaming. It’s a comment written by a teenager who used to play lots of racing games with his dad on the XBox until his dad passed away:

“When I was 4, my dad bought an XBox. We had tons and tons of fun playing racing games together - until he died, when I was just 6. I couldn’t touch that console for 10 years. But once I did, something incredible happened. I found a GHOST.”

What happened was that the console had recorded the fastest lap as a ghost driver, and this ghost driver was his dad. Even though he was already dead for 10 years, he was still racing around the track – transporting him forward in time so that his son could race him like they used to. I think that our data is like a ghost driver. The marks we’re making and the traces we’re leaving – they’re all turned into this recording of ourselves, our identity. And we can observe it, or even compete with it if we choose. Through our data we’re creating a hologram of ourselves; a digital twin.

Crossing the streams

Self-tracking is more than just collecting numbers about ourselves. Data is not useful in itself. It’s when we turn data into information that it becomes useful. One of the ways of doing that is context. When you combine different layers of data, you’ll get some interesting insights.

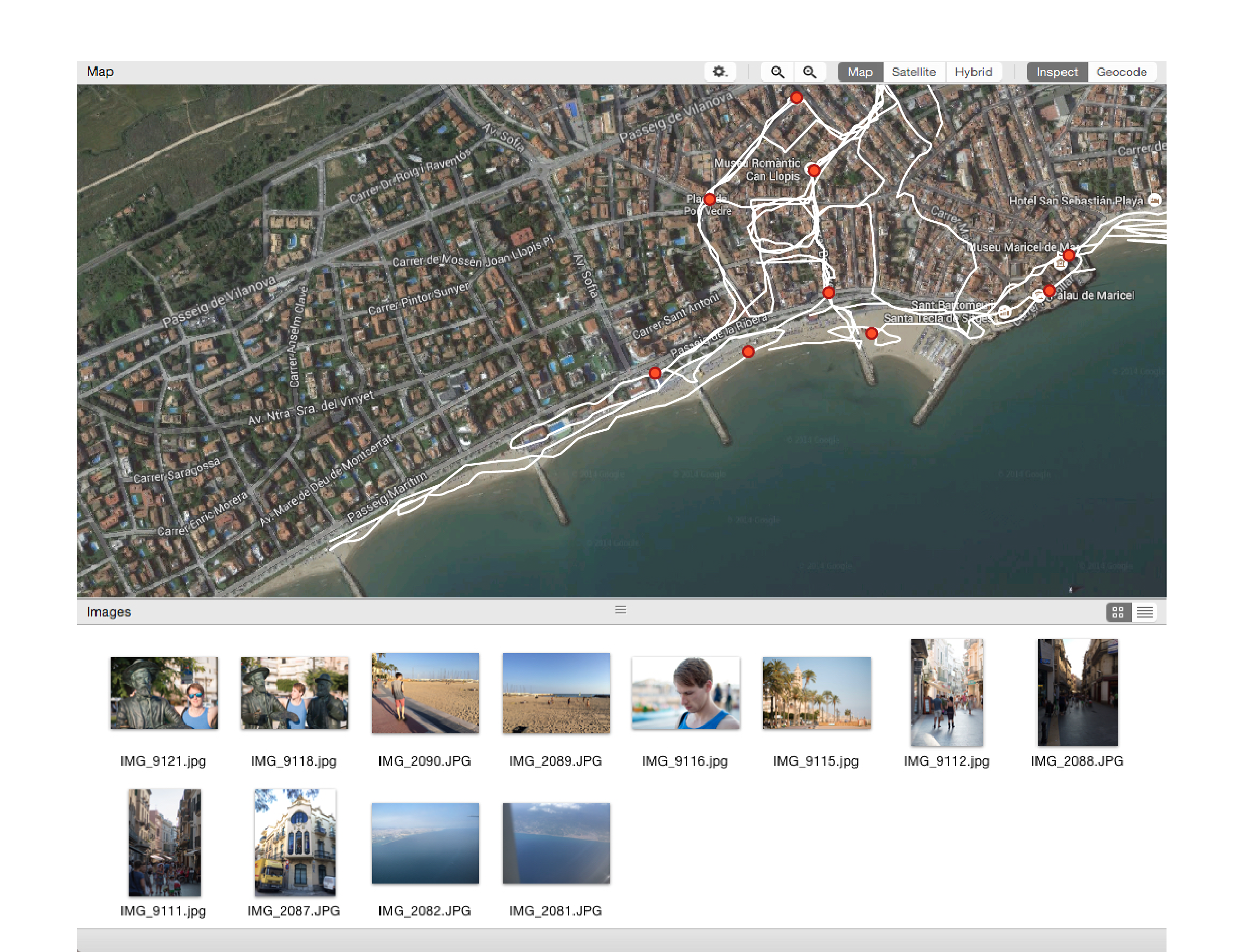

Let me give you an example: I talked about photos as evidence of specific moments that I choose to capture for posterity. I’m sure everyone can relate to that, even if you’re just capturing holiday snaps. What’s in between any two of those photographic moments is rarely consciously captured. Two photos of an event may be enough of a cue to help you recall an experience, but when you combine it with other data you get a much higher resolution of that memory. When you plot your photos on a map, along with your movement or activity track, you may uncover the story of how you circled the town centre in search for suitable dinner options. Or the walk you took along the beach, where you didn’t take 100 photos of the same seafront but which is captured accurately in your movement data. Now add your Last.fm tracks and you've even got a soundtrack for your memory.

Data tells a story just as much as photographs do. I think Chris Dancy is on to something when he says: “your future selfie won’t be a picture of you on a roller-coaster; it will be your heart rate and blood work showing your authentic fear”.

The age of lifelogging is a new age of journalling, where the journal of our lives is written for us by our data in an automatic, almost effortless and near-complete fashion.

The future of reminiscence

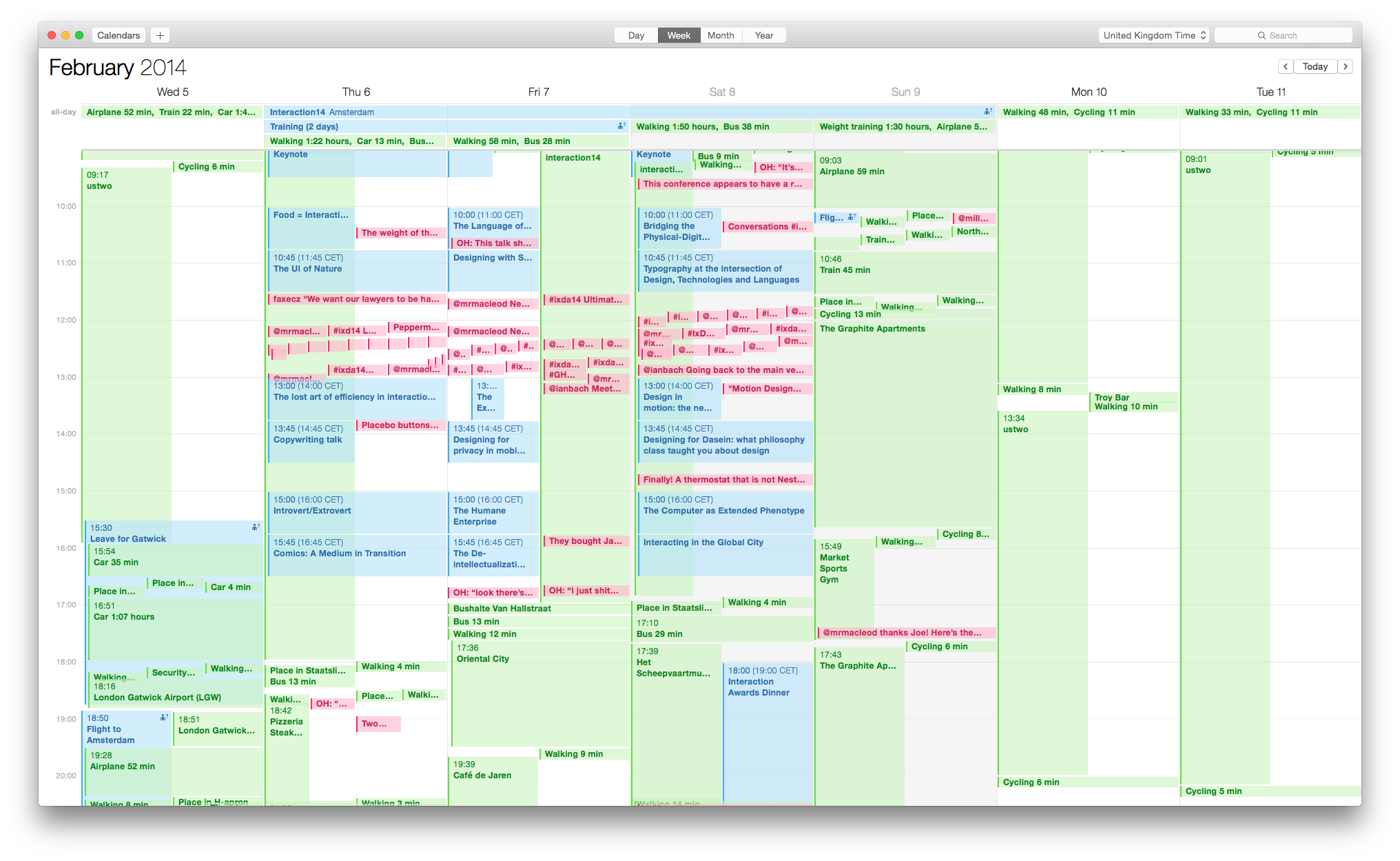

I have tens of thousands of photos on my hard drive, the earliest is from the month and year of my birth. I’ve been digitising receipts, invoices, bills, bank statements and other written correspondence throughout my life, using just my iPhone – they’re now all searchable PDFs. Then I started plotting most of these things on a calendar, and that’s the same calendar that all my current data feeds and social media activity are automatically merged into using tools like IFTTT or MovesExport. This is effectively the time machine I was talking about, because now I can jump to any date in the past and re-discover stories. I could revisit the experience of going to a conference earlier this year. My activity data and planned events bring back the memories about the mad rush to get to the airport, arriving at the gate a minute after the scheduled departure time. And I can also see which sessions at the conference I felt compelled to publicly comment on – evidently, lunch time was the most communicative, with a cluster of tweets sitting boldly in the middle of the conference day. This simple journalling technique brings together prospective memory, activity and opinions at a particular point in time and visualises effectively what I had planned, where I actually was, and what I was thinking or saying.

This may be a trivial example, but I think reminiscence is a powerful concept.

A great amount of research has been done for people living with Alzheimer’s and dementia, for example, where “reminiscence therapy” has proven to be extremely rewarding and valuable. It has shown to help reduce depression, increase social engagement, instil a sense of purpose, meaning and identity and build stronger bonds between patients and their families or carers. And all these benefits apply to healthy people too.

In fact, people all over the Internet recognise this. This is why Throwback Thursday is an extremely popular Internet meme. Every Thursday people around the world share an old photograph of themselves via social networking sites and image-sharing communities like Instagram. And there are a number of apps and services that tap into this behaviour. Apps like Timehop, Memoir and others that let you rediscover content you shared in the past and reminisce about your memories, both on your own and together with your social network.

Reminiscing lifts our mood and strengthens our sense of self-worth and identity, and it helps us build stronger bonds with those around us.

Research has shown that we remember more events from late adolescence and early adulthood than from any other stage of our lives. In psychology this is known as the reminiscence bump. Perhaps then with a trend towards ubiquitous data and the Quantified Self contributing to more accurate and more complete memory cues, the reminiscence bump may not even be noticeable for this and future generations – because we can turn to technology to augment our biological memory.

With the prospect, however, of essentially outsourcing our memory to the Apples, the Googles, the Facebooks and the Dropboxes out there, there are also some far-reaching implications that need to be addressed, and I will talk about these in another post.

Final words

We live our lives through digital services and connected devices and generate data at an unprecedented volume. Whether you’re actively self-tracking or not, we’re all capturing traces of what we do every day. They’re like photographs of every moment of our lives. They form a hologram of ourselves reflecting our experiences - our memories. Reflecting and reminiscing through these memory cues can be powerful.

“Memory is a rope let down from heaven drawing one up from the abyss of not-being" said Proust. This means our memories make us who we are. We need to take good care of them. I hope that this inspires you to pay attention to these digital traces of our existence and to treasure them.

Time travel is a reality.

Read the follow-up post here