This reflection has been adapted from a side-event held after The Conference in our Malmö studio this year.

As a software engineer and creative technologist here at ustwo, I like working on things from web frontends and infrastructure, to open source maths libraries for computer graphics, and I’m very fortunate to work with amazing teams building digital products.

But today—reflecting on my time at The Conference—I’d like to talk a little bit about time itself, and specifically anachronism: things being outside of their regular place in time. I also believe much of what you will read in this post are things we humans do have quite a strong intuition for. In fact, this week I learned the word Chronoception from Grace Boyle’s talk during the Spatial Computing breakout, which describes our sense of time. Even so, I think there is a lot of value in building a vocabulary around this intuition, so we can be more explicit, communicative, and collaborative about it.

Language as a tool to shape the future (looking ahead)

Just like many of the speakers and attendees at The Conference this year, I love thinking about the future. Maya Indira Ganesh, in her talk during the (Artificial) Intelligence breakout, used this concept of a “temporal metaphor” when referring to AI—the idea that it can be used as a tool to “catch up” with an unevenly distributed future. I was fascinated with this idea, and found it a great example of the inherent anachronism that we constantly have to deal with. Alongside other talks, it made me think a lot about how we conceive of the future, which is kind of back to front and front to back and from the sides, simultaneously. Hopefully that will make sense as you continue reading.

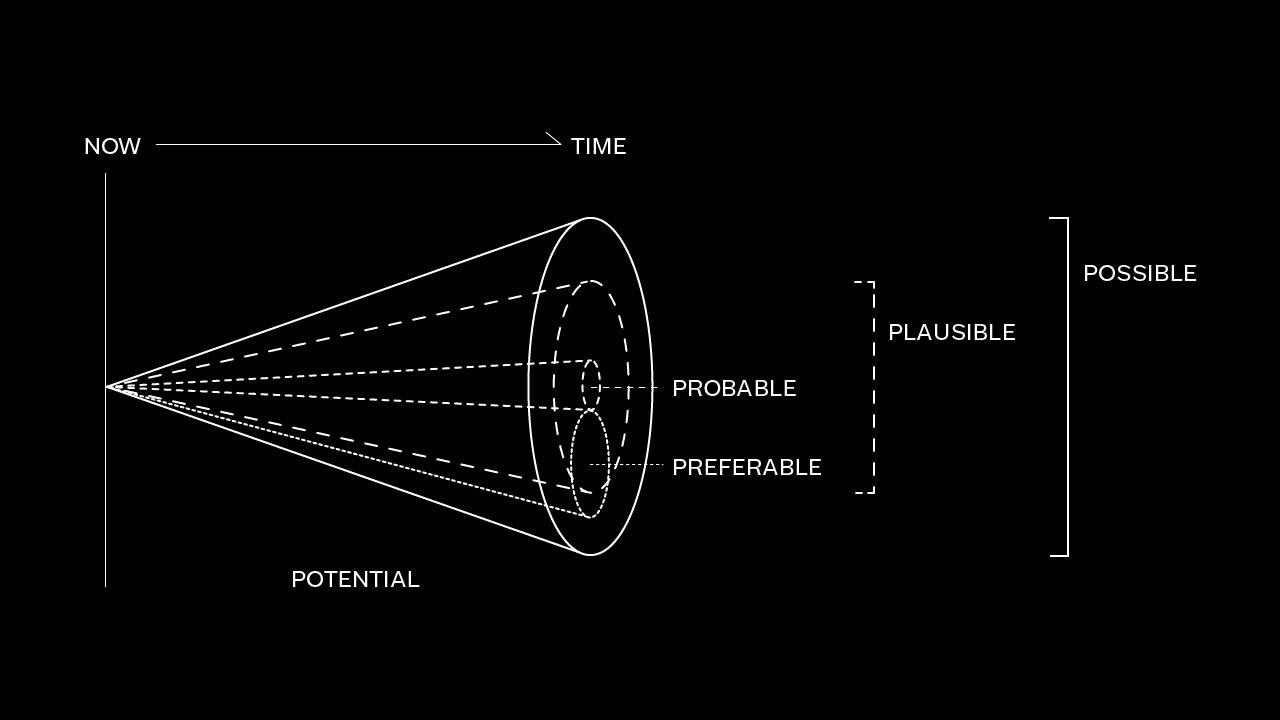

This is a Futures Cone. It’s a visualisation that’s been used to depict alternative futures for a number of decades. I first came across it via the book Speculative Everything, by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. We have the present at the vertex of the cone on the left, and all possible futures contained on the right. Within this range of possible futures are subsets for probable and preferable ones, among others.

The challenge we have when creating products isn’t just how to chart a path from the left to the preferable section on the right. It’s also discovering what that section even is. The visualisation you see above assumes that ‘preferable’ is a known area, but I think in most cases this actually isn’t true. To know what ‘preferable’ means, we need to be looking far ahead, and then work backwards, before knowing what to do soon.

Another way to think of a preferable future is as a north star vision. Creating one is a big part of the discovery projects we do at ustwo, and requires a lot of thought, research, and care. A north star vision is a determination of what you want to see. It is outcomes-oriented and can be flexible in terms of implementation, but should always provide an anchor within the preferable range of futures. For example, for some recent work we did to create The Body Coach App, we envisioned a world where nutrition and fitness could be engaged with by absolutely anybody, and are in the sole service of your health and happiness. For someone like Liam Young, who spoke during the opening Sense and Sensibilities seminar, perhaps this north star is the vision of ‘Planet City’ that he shared with us.

When you have an anchor in the future, you also have a direction of travel. And in our world of building digital products, it’s wise to be iteratively stepping forwards to reach your vision, and learning more along the way (something we call continuous discovery). While it’s easy now to think that this direction means you’re dealing with a linear future, there’s a real danger of missing the mark by only thinking forwards in time. We should always be thinking about the shape of the cone itself, and how to affect it. This is where constraints come into play.

A constraint could be something simple like using an existing design system or opinionated programming framework. Things that limit the range of possible futures by helping you avoid common problems. Constraints can also be more abstract, like a corporate mission statement. Some constraints may be absolute requirements, and others may be voluntary. Tessa van Soest from B Lab spoke about the B Corp certification process, which is a constraint we’ve imposed on ourselves at ustwo. Through the process, we formalised a lot of our ideas around ‘doing good’ in the world, introducing new policies and commitments that constrain this set of futures for the business, narrowing them closer around what we deem preferable.

While our starting point and north star might not have changed, the constraints have an effect on the potential shape of futures. This is topology, the geometric characteristics of something that can be deformed, while maintaining the connections within.

I did some research while reflecting on all the conversations about the future during The Conference, and I found that there is a wealth of vocabulary and formulae that scientists have created to describe the topology of spacetime. Much of this went over my head, but what I did find interesting is that I couldn’t find any equivalent language for the way that we intuit time in our minds, which can be without order and in multiple directions. There’s a bit of a linguistic gap.

And so I think that as people who care about the future, and who want to create a better one, it’s important to try and plug this linguistic gap. To try and to share our constantly evolving understanding of a project, critique, or artwork, in ways that approach time more fluidly. We should be embracing the chaos, texture, and dimensionality that is contained within our perception of the future, with ourselves and with our peers. From the present forwards, from the future backwards, and from the constrained sides, at the same time.

Searching the past to find a view (reaching behind)

While I’ve shared a little about looking ahead to conceive our futures, I think it’s also important to consider how everything that’s come before also shapes what we see. How the seemingly linear past frames our personal cone of futures. Hopefully, you won’t be too annoyed at me for now trying to argue that the past is also not linear. Jordi Roca gave a great example of this during the opening talk of The Conference, when speaking about how memories from our past can be viscerally launched into our present with just a smell. I think this concept also manifests itself quite clearly in our work.

For many of us in the world of design and technology, we are generalists who may have a pretty varied set of experience, and it can be quite hard to bring it all to bear in our work. Often we, and others, only value our most recently acquired abilities. This has certainly been the case with me, having recently moved fully to a software engineering role after a few career ‘false starts’.

Coming back to our views of time, I like to think that what’s come before has created the lens through which you construct the future. It gives you a unique perspective, and also limits what you can see. For me, that lens is comprised of my time studying physics, selling tickets and sweeping floors in a cinema, and my upbringing in the North-West of England, among other parts of my past. These are characteristics that I used to think of as pieces of baggage that stretch increasingly further back in time, and are therefore decreasingly impactful on my life and work today.

But now I’m not so sure about that. While we may use specific skills from our past quite rarely, that doesn’t mean that the way this baggage has crafted our view of the world is diminished. It’s just as important now as it was then. I like to think of this as ‘baggage collection’, something that is done after transiting between spaces.

My colleague Jim and I were remarking recently, that a generalist product designer who comes from an industrial or graphic design background actually has very specialist experience, and that their current role is about applying it to general problem areas. I’m sure there are also plenty of similar examples across other industries. The self-styling as a generalist may be a useful signal in many instances, but it can also do a disservice to your past.

In my case for example, I find the way I collaborate on projects has been impacted more by my time in customer service—working in teams to make sure a movie theatre runs smoothly and that viewers have a great time—than my experience as a technologist. Unfortunately this is a characteristic that doesn’t always spring to mind when people think (stereotypically) of software engineers, yet it’s a huge part of my work at ustwo.

And when you look at your past this way—not being linear and with everything equally contributing to your abilities and unique lens of the world—you may find that the generalist/specialist divide breaks down a little. Those with very generalist roles can be seen as having a specialist view, and vice versa. And what I think is most important about ‘lens thinking’, is that it encourages you to confront limitations in what you are able to see. Those who saw Tega Brain’s talk, The Environment is not a System, may remember her point that a history of technical solution making leads to seeing things with a systems view, which is not always the best, as she pointed out in the case of ecological research.

The pasts of others, both those we know and those from history, also intersect with our views of the world. Nick Seaver brilliantly illustrated this during his talk in the (Artificial) Intelligence breakout session, by drawing parallels between the addictive algorithms that tech companies create today and the animal traps that have been crafted for thousands of years. His talk highlighted that inventions from the far flung past give as real an insight into our world today as thoughts from just yesterday, another anachronism. This parallel informed some questions: who are we learning from? What were their views? In essence, whose past is now intertwined with your past, and how does it affect your future?

Back to the present (standing still)

I never expected to sum up a tech conference with a thesis on the topology of our understanding of time, but here we are. As you can tell, my experience at The Conference has made me think a lot about temporality, how there are multiple futures, and also multiple pasts. With all this in mind, it strikes me that the only thing we can be certain of as being singular, is our present. Embracing the complexities of our pasts and futures, and how they shape our thinking, is something I now plan to do with it.