This is a guest post written by Peng Cheng, founder of PauseAble. The latest interactive meditation experience – Sway – is now available on the App Store.

Embedded content: https://vimeo.com/210642044

We perceive the world around us through the five basic senses - sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch.[1] Through these senses, external stimulations can capture and manipulate our attention. In this digital age we are living in, information and exciting experiences are designed to compete for our attention. It’s easy to feel constantly distracted and affected by the external world, and lose touch with ourselves and our body.

However, lesser known than the five external senses, we have another remarkable sense. One that is fundamental to our function and being, and holds the key to creating a healthier and more constructive relationship between digital technology and our well-being.

The forgotten sixth sense

In addition to the five external senses, we also possess an internal sense of our body and movements. Scientifically referred to as proprioception, but often called the ‘sixth sense’, it’s essentially awareness of our body’s movements and the ability to change our movements “on the fly” based on additional inputs received from our visual and tactile sensory organs.[2]

What’s remarkable about proprioception is that it is also an integral part of our voluntary muscle control system and the reason why every physical activity we perform can potentially be executed with precision and grace [2]. This means that when we become conscious of our body, we have complete control of how our movements will unfold from moment to moment. Since ancient times, conscious control of body and movement have been a vital part of mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness and bodily movements

According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, mindfulness is awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.[3] Mindful bodily movements help practitioners sustain focused attention for a longer period of time in order to improve the stability of attention. The most prominent example of this is the Chinese meditative martial art Tai Chi, which is often referred to as ‘Meditation in Motion’. With full recognition of its profound philosophical roots, practitioners voluntarily move their bodies in a slow, continuous and gentle way in precise patterns which are particularly designed for combat, increasing flexibility, and strengthening one's muscles.

Various forms of physical artefacts have emerged in different schools of contemplative practises – such as the Chinese meditation ball, Buddhist prayer beads, Tibetan prayer wheels and Tibetan singing bowl. They all invite practitioners to sustain slow, gentle, continuous mindful bodily movements, to anchor focused attention in sustaining the movements for a longer period of time. These artefacts are often used on the go as complementary practises of formal sitting meditation.

The physical artefacts of ancient mindful movement practises are often derived from their respective religious aesthetics and philosophical roots. They are elegant and effective, but are sometimes less capable of bringing benefit to people outside their religious beliefs. And when learning Tai Chi, a beginner will most likely focus on learning its forms and patterns which are difficult to remember and take time to become familiarised with.

An underlying principle

Beneath the variety of physical forms and patterns, there is an underlying principle that enables many mindful movement practices which is: Voluntarily controlling the muscle system by performing slow, continuous, and gentle bodily movements for longer periods of time will result in improved focus, clarity, and help one achieve relaxation.

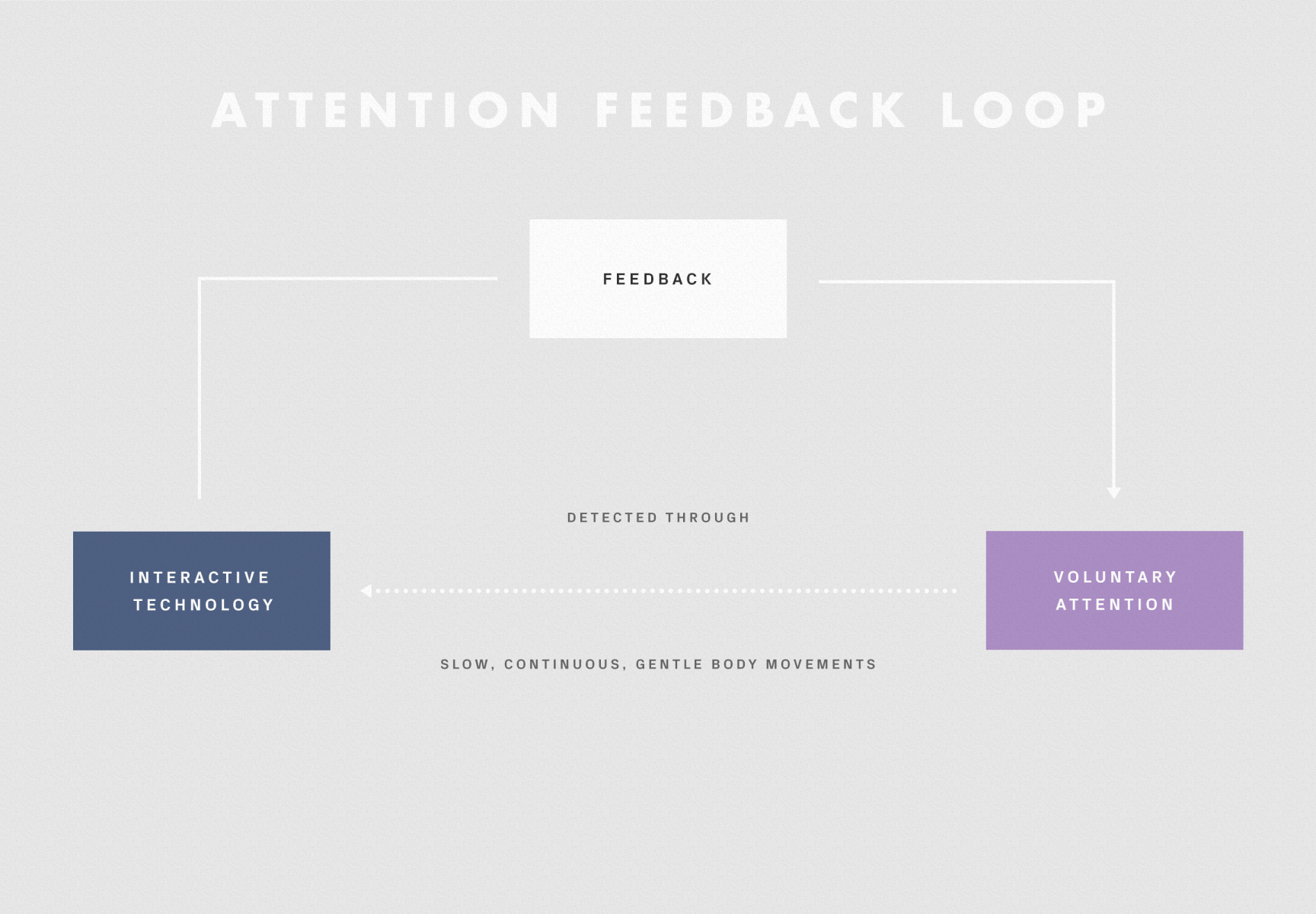

This principle is not connected to any specific practises and can be applied to every movement we make. This allows for mindful movement as a general practise to be truly interwoven into our lives. At the same time, it’s easy for modern interactive technology to sense slow, continuous and gentle bodily movements, which enables us to detect voluntary attention in a simple and effective way. This opens up a truly unique opportunity for interactive technology to effectively facilitate mindfulness practise without requiring expensive biofeedback monitors (such as brain scanner, or breath monitor) for the very first time.

The interactive meditation framework

The reason why there has not been a simple and practical way for interactive technology to facilitate mindfulness meditation is because there hasn’t been a way to detect the subtle inner quality of voluntarily focused attention.

However, our unique approach enables technology to detect voluntary human attention through slow, continuous and gentle bodily movements for the first time. This allows interactive technology to do what it does best: engage humans with a purposefully designed activity, in this case, mindfulness practise for an extended period of time, with carefully designed digital feedback. We call this an attention feedback loop, and it serves as the foundational framework of interactive meditation. This framework is firmly rooted in the following existing scientific fields:

Attention Restorative Process (Psychology)Professor Stephen Kaplan from University of Michigan proposed two mandates underlying different attention restorative processes:

- Avoid calling on tired cognitive patterns, by being away from everyday environment.

- Avoid unnecessary effort. Running a single cognitive map for an extended period of time is ideal for attention restoration.[4]

For interactive meditation, we use digital design to create a beautiful ambient audio-visual environment that is engaging yet non-stimulating to our mind. The mindful body movement gives people a single cognitive map, which does not strain their cognitive effort unnecessarily. Importantly, the rewarding digital experiences are only available to people when the technology detects a person’s focused attention through mindful movements. This way, the digital experience gives meaning to the act of focused attention, which motivates people to keep going for an extended period of time.

The Relaxation Response (Physiology)In 1975, Professor Herbert Benson from Harvard Medical School introduced the concept of relaxation response which counteracts the stress response. It’s a coordinated physiological response characterised by decreased arousal, diminished heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure, in association with a state of “well-being”.[5] An essential aspect is that the relaxation response can be elicited by anyone, as it is a self-regulative process.

There are only two elements required to elicit the relaxation response:

- the person directs and pays attention to the repetition of a word, sound, phrase, prayer, or muscular activity, and

- the person passively disregards everyday thoughts that inevitably come to mind and returning to your repetition.[6]

In interactive meditation, we build upon the repetitive muscular activity by using slow, continuous and gentle movements as the object of attention. When people are distracted by everyday thoughts, it becomes difficult to sustain the focused movements, which can be easily detected by technology. This way, we can design the digital experience to remind people to bring attention back to the focused movements again and again and trigger the relaxation response in the body.

The interactive meditation tool

A lot of people argue that mobile phones, the most predominant form of interactive technology, are making our lives increasingly distracted and stressful. This is because of the way mobile interactions have been designed – to be as fast, intuitive and efficient as possible – where the interaction journey is minimised to almost zero, and make us addicted to the unlimited content and experiences it provides.

In fact, the mobile phone is an ideal platform to realise interactive meditation. What’s remarkable about mobile phones is that they unite both advanced sensing interfaces (touch, motion, voice, light) as well as feedback interface (visual, sound, haptic) into one compact form that fits into everyone’s pocket. It means the mobile phone itself is capable of detecting mindful bodily movements while at the same time providing real-time digital feedback to encourage people to sustain these mindful movements for a longer period of time. With its extremely well-established accessibility, mobile phones can bring the benefit of mindfulness through interactive meditation to the masses in a simple and cost-effective way.

Interactive meditation vs guided meditation

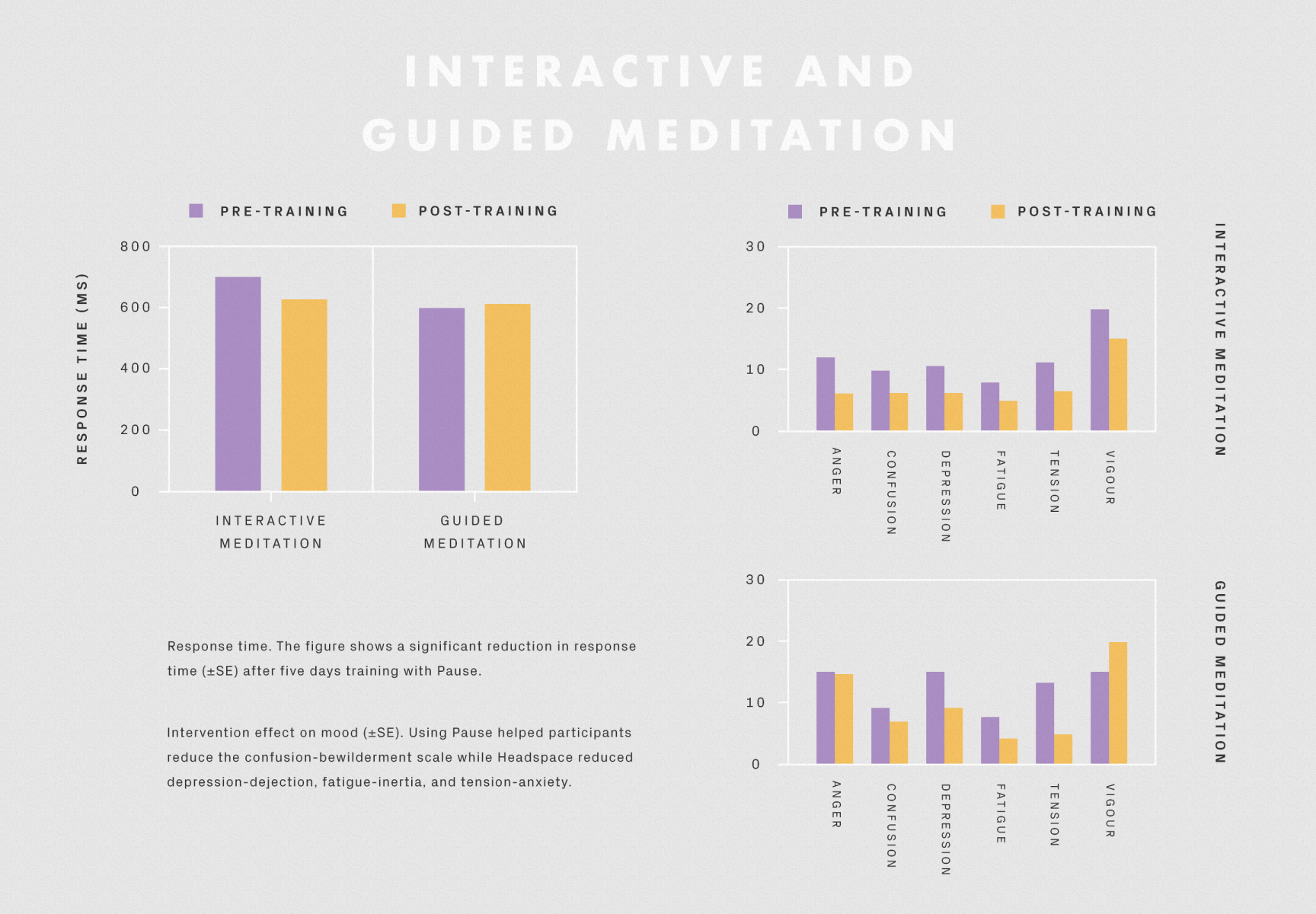

Guided meditation has become a popular way of practising mindfulness; it is effective and powerful, but often requires dedicated time and a private place. In order to understand and validate the effects of interactive meditation compared to guided meditation, we collaborated with scientists from the Centre for Human Engaged Computing at Kochi University of Technology in Japan.

We used PAUSE as a case study of interactive meditation and compared it to guided meditation in both quiet and noisy environments. The results were measured using EEG and heart rate monitor and show interactive meditation works significantly better in noisy and busy places, while having similar positive effects as guided meditation in quiet places.[8] We also found that engaging in interactive meditation for 20 minutes a day for 5 consecutive days significantly outperformed guided meditation in reduced attentional response time.[8]

With this scientific evidence, we see interactive meditation playing an important role in modern society, allowing people to experience the benefits of mindfulness meditation on the go anytime, anywhere.

Research through building products

We launched our first product PAUSE - Relaxation at your fingertip in October 2015, which focused on touch input and screen interaction.[7] The simplicity of the product and the stunning visual and sound feedback made PAUSE a success. It was #1 top selling app in 18 markets, ‘Best of 2015’ in the App Store and top 10 apps by TIME.com in 2015. It has been officially downloaded more than 400,000 times and is helping people around the world coping with stress, anxiety, PTSD, addiction, insomnia, and anger issues.

Now, with the launch of SWAY, we open the interaction possibilities from touch into a full body experience where every movement you make is an opportunity to practise mindfulness. SWAY uses the motion sensing capabilities of the phone to detect mindful bodily movement. You can do subtle wrist movements, expressive arm movements, or put the phone into your pocket and subtly sway your body or take a mindful walk.

With PAUSE and Sway, we’re showing how this new interactive meditation approach can turn mobile phones, the most stressful product we have, into an effective mindfulness tool and bring focus and calm to users anywhere, anytime. As Pico Iyer beautifully said: “in an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow. And in an age of distraction, nothing is so luxurious as paying attention”.[9] We hope the introduction of interactive meditation will inspire a new generation of interactive products that are designed not to compete and consume our attention, but to restore and cultivate our attention, and leads to greater well-being in the society.

References

- http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/46796/title/Proprioception--The-Sense-Within/

- Proprioceptive training - a review of current research, Caroline Joy Co, 2010 by Rehabsurge, Inc.

- http://www.mindful.org/jon-kabat-zinn-defining-mindfulness/

- Stephen Kaplan. 2001. Meditation, restoration and the management of mental fatigue. Environment and Behaviour 33(4), 480-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973106

- Neema M. Moraveji. 2012. Augmented self-regulation. Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University.

- Herbert Benson and Miriam Z. Klipper. 1975. The Relaxation Response. Avon.

- Peng Cheng, Andrés Lucero, and Jacob Buur. 2016. PAUSE: exploring mindful touch interaction on smartphones. In Proceedings of the 20th International Academic Mindtrek Conference . ACM, 184–191. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2994310.2994342

- Kavous Salehzadeh Niksirat, Chaklam Silpasuwanchai, Mahmoud Mohamed Hussien Ahmed, Peng Cheng, and Xiangshi Ren. 2017. A Framework for Interactive Mindfulness Meditation Using Attention-Regulation Process. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, In Press.

- Pico Iyer TED talk: the art of stillness. https://www.ted.com/talks/pico\_iyer\_the\_art\_of_stillness/transcript?language=en