On the surface, the application of game design principles to learning feels like a “solved problem.” You cook up a points system, you set up a leaderboard, and before you can say “gamified engagement mechanisms,” you’ve turned your user base into a gaggle of badge-obsessed Gollums, ready to fight tooth and nail for their precious streaks.

As you might have guessed, we aren’t big believers in this approach, and we’re not alone in our skepticism. In broad terms, our view is that standard gamification transplants surface-level game elements into products with little regard for users’ core aspirations (why they come to a product) or their emotional responses (why they grow to truly love it).

The good news is, when we venture beyond the shallows of gamification, we see that games and game design do offer plenty of valuable lessons for product designers in the education space. From creative reframing of “stakes” to reduce the anxiety associated with tackling unfamiliar concepts, to harnessing human curiosity for perseverance in problem-solving, there are many ways to leverage the power of play to deliver better emotional experiences and functional outcomes for users and businesses alike.

We call this Play Thinking, and in this article, we’ll dive into one key aspect of how this philosophy drives engagement and reduces drop-off for products in the learning space.

Play can reduce the anxiety associated with tackling unfamiliar concepts.

When we think play, we typically think positive: fun, rewards, and moments of delight. All valid, but it’s key for us to recognize that play also helps people manage negative emotions (if you’re interested in diving deeper into this topic, we have a whole article dedicated to exploring it in the context of health). Attempting to learn something new often brings an array of negative emotions. One of the most “powerful”, in terms of driving disengagement from learning, is the self-doubt that arises when approaching an unfamiliar, complex concept. It is a massive barrier to educational engagement as well as a major driver of drop-off.

For clues on how to solve this problem, we must look to its roots. The evolutionary response to the unknown is fear and caution. And, for most of history, avoiding the unknown was a great idea. See an unfamiliar stringy thing slithering towards you? Better climb that tree. Hear a weird sound? Run (into the) forest, run!

And while quadratic equations and programming languages may not inspire the same mortal terror as the unknowns of old, our ancient sense of foreboding manifests as modern anxiety — the sense that we are not up to a challenge, that we are impostors, that it is better to distance ourselves from an unfamiliar, uncomfortable thing than to engage with it.

So, how can Play Thinking help us combat the intimidation and anxiety that arises from the unknown? It provides us with two great weapons: the power of pawing, and of pretending.

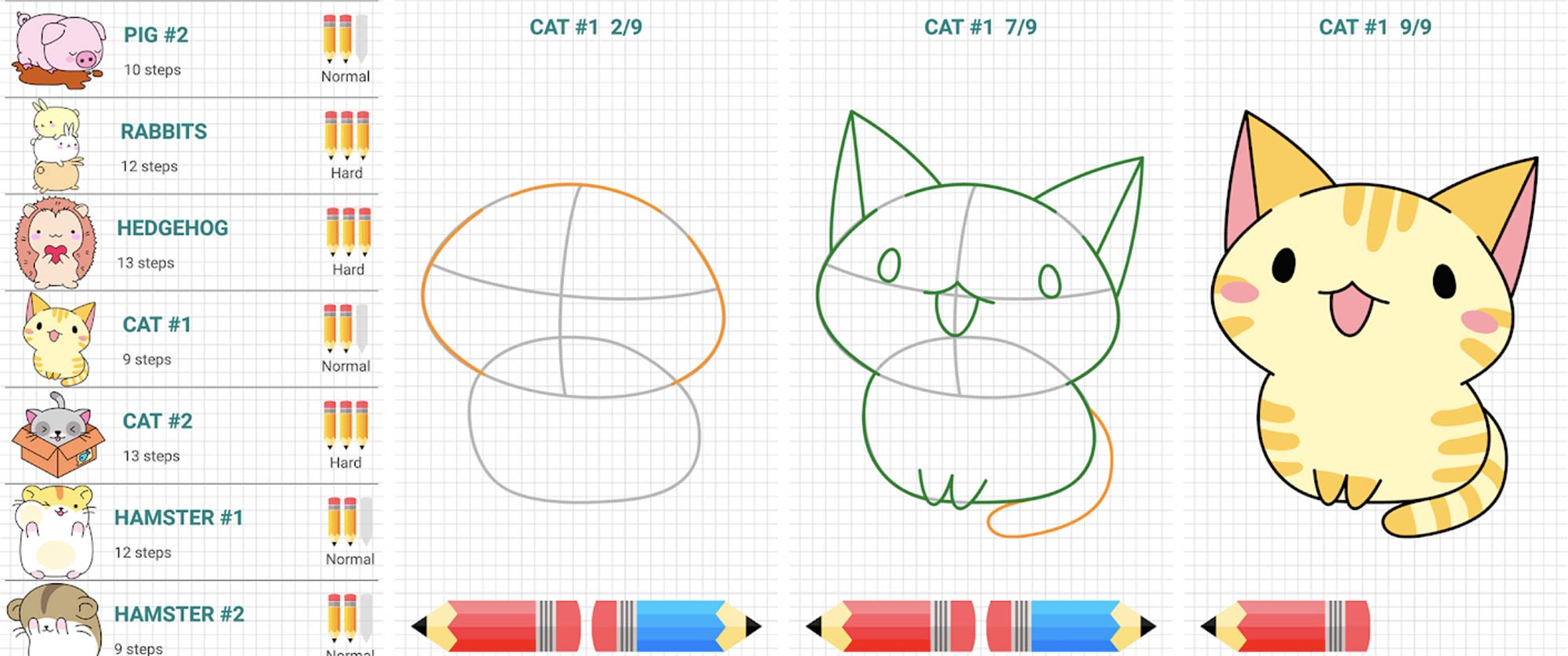

Take the action of “pawing”. You’ve doubtless seen cats and dogs do it to “feel out” and familiarize themselves with a strange new object. In design terms, it means enabling piecemeal, progressive engagement — guiding users through a process of breaking down concepts until they’re no longer scary. In educational terms, its counterpart is progressive mastery, and its techniques and benefits are well-documented.

The power of pretend: cultivating self-belief and sustained engagement through empathetic design.

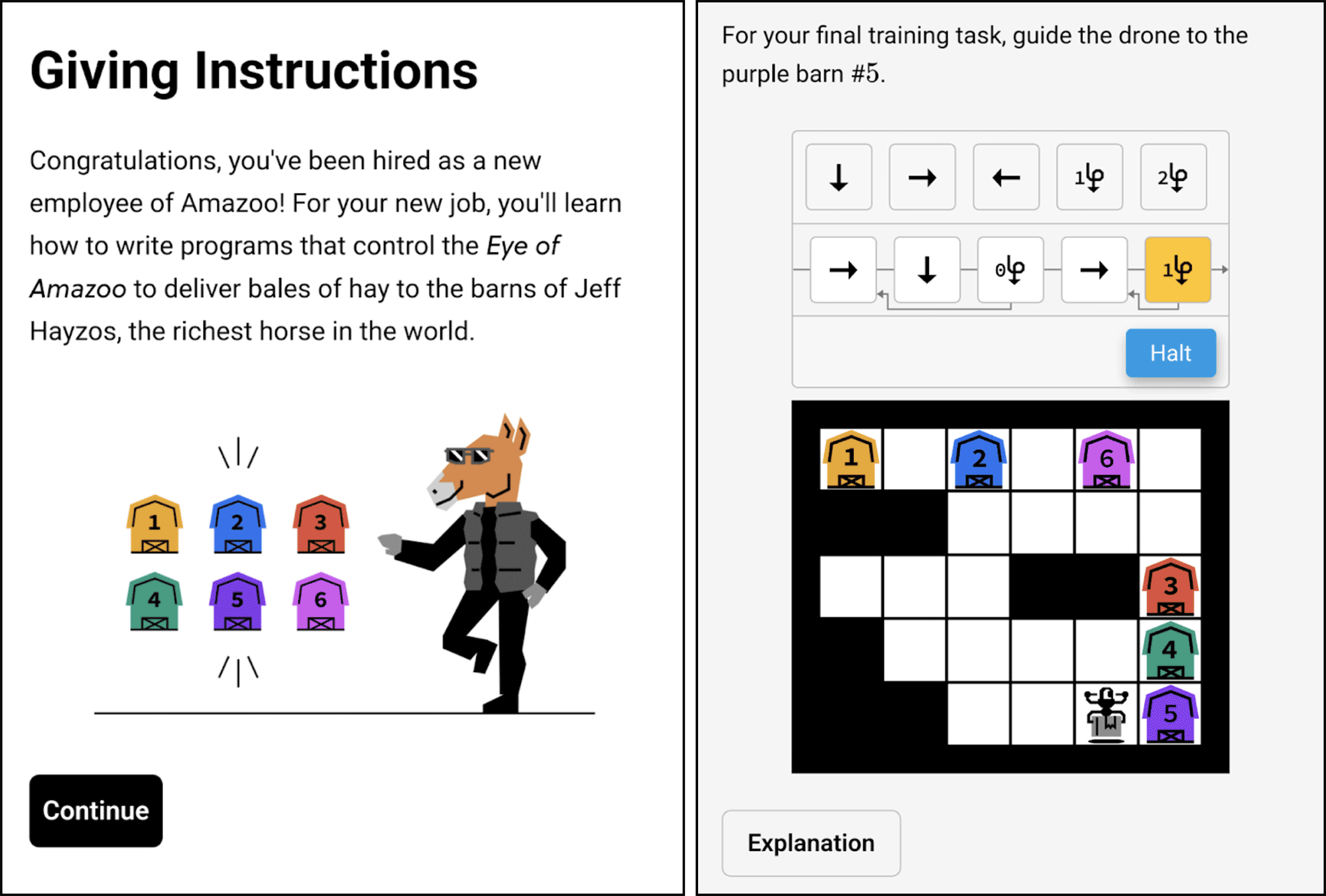

“Pretending” is a little more complex than pawing. In design terms, it means reframing the “stakes” of a scenario, such as a challenging quiz question, into something more attractive to the learner. Pretending has a simple “look” component and a more nuanced “feel” component. The “look” component incorporates appealing narrative and visual cues to “dress up” a concept in an aesthetically pleasing wrapper.

There’s nothing wrong with the “look” component of pretending, but the true power of pretending lies in transforming both the look and feel of a concept or problem. Transforming the “feel” means transforming the emotional responses inspired by a challenge. In practice, this resolves anxiety and self-doubt and turns intimidation into excitement, empowering the user to believe they have the abilities and tools to tackle the challenge.

Fundamentally, this is mindset transformation, and it can be achieved in many ways. One approach entails creative reframing of the user’s self-image — reminding them of how far they’ve come, what skills and ideas they have accrued already, and suggesting how they might apply their well-earned mental equipment to summit the next peak.

Alternatively (or, ideally, additionally!) the challenge itself may be “pretended” into something that feels very different. Instead of an unforgiving “pass/fail” gate, the process of grasping a concept may be reframed as a winding journey through an awe-inspiring landscape, where wandering off the trail doesn’t represent a “wrong turn”, but rather a well-trodden path of discovery, whose exploration yields a holistic appreciation and understanding of the overall “concept-scape.”

Conclusion

The possibilities of Play Thinking are as deep and expansive as the spectrum of emotional experience. And in the age of AI, where functional questions and conventional solutions are increasingly a “solved problem”, the value of emotion-centric design and creative thinking will only continue to grow. Ultimately, though, the benefits of Play Thinking for designers are less important than the benefits for users: more positive learning experiences, more supportive learning environments, and, of course, better learning outcomes.